Where Perception Meets Measurement: Unlocking True Multiomics with Semi-Permeable Capsules

Scientific progress has always depended on how deeply we can see. Each new tool – from magnifying lenses to sequencers – has revealed another layer of biological reality, reminding us that perception defines what we call truth. Today, the challenge is not seeing individual layers but connecting them. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) maps transcriptional diversity, yet leaves the genomic causes and functional consequences unresolved. True multiomics demands technologies that can observe genotype, phenotype and more in the same cell, across multiple biochemical steps, without sacrificing throughput or integrity. Semi-Permeable Capsules (SPCs) make this possible.

Each capsule acts as a selectively permeable microcompartment where small molecules diffuse freely while cells and long nucleic acids remain encapsulated. This design allows sequential reactions (lysis, amplification, labeling, and sequencing) to proceed under optimal conditions within the same compartment. By unifying molecular layers, SPCs turn single-cell analysis into a continuous experiment rather than a fragmented workflow. They reveal how mutations shape transcription, how clonal diversity drives tumor evolution, and how extrachromosomal elements connect to microbial hosts. In doing so, SPCs remove one of biology’s final technical constraints – the container – and open the path toward a truly integrated understanding of the cell.

Reality as We See It

What we call reality is always filtered through perception. By definition, perception involves recognizing and interpreting sensory stimuli – our mind’s way of constructing the external world (Kelly et al., 2019). Yet perception is never static; it depends on attention, context, and imagination. Imagination takes us even further: it allows us to envision what lies beyond what we can touch or see. Each of us experiences a unique version of reality shaped by inner and outer worlds, by what we sense and what we know (The Perception Census, 2023).

But in science, perception is not enough. We seek truth – something that remains factual and consistent regardless of the observer, and defined criteria to verify true statements by experiments and by the simplicity of theories (Brüssow, 2022). Through centuries, the curious minds have asked the same question: when we measure, are we seeing truth or merely its projection through our instruments? This question is at the heart of modern biology. Every new tool – from magnifying lenses to sequencers – has revealed another layer of biological reality, reminding us that perception defines what we call truth. So what is the true reality in science? One way we get closer to it is through multiomics – by observing life across its molecular layers rather than through a single lens. Multiomics is an attempt to reconstruct biological reality from its overlapping dimensions. We no longer ask only what genes are expressed, but which mutations drive those expressions, which proteins act on those signals, and how these interactions shift as cells divide, age, or adapt. Each layer brings us closer to truth, yet each also exposes how partial our view remains.

From Single-Cell Genomics to Multiomics

Why multiomics and why now you may ask? Single-cell technologies revolutionized biology by turning populations into individuals. Instead of bulk averages, we could finally observe how cells differ in identity, state, and trajectory. Yet, despite its power, single-cell genomics offers only one layer of reality.

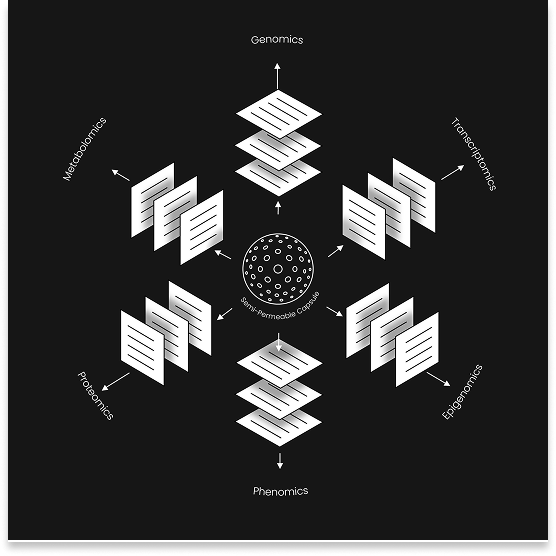

Multiomics combines different layers of molecular information – genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and beyond – to reveal how they interact within the same biological system (Choi et al., 2021; Hartmann et al., 2023). By integrating these “omes”, we can identify novel biomarkers, uncover geno-pheno-enviro-type relationships, and understand how molecular networks give rise to phenotype (Choi et al., 2021). As Hasin et al. (2017) describe, the integration of multiple “-omic” datasets marks a paradigm shift in biology, enabling an interpretive rather than merely descriptive science. With multiomics, we move from listing components to reconstructing systems. Recent work further shows that multiomic approaches at the single-cell level enable unprecedented insights into cell-specific signaling, differentiation, and interaction (Hartmann et al., 2023).

However, integrating such layers remains technically complex. Omics platforms differ in chemistry, dynamic range, and data scale. Batch effects, normalization, and signal sparsity challenge reproducibility (Sahu et al., 2022). The biggest constraint is often physical: the container. If each molecule type requires a different chemistry, how can we measure them in the same single cell?

...

Continue to the full piece here [SelectScience]